Blast Overpressure (BOP)

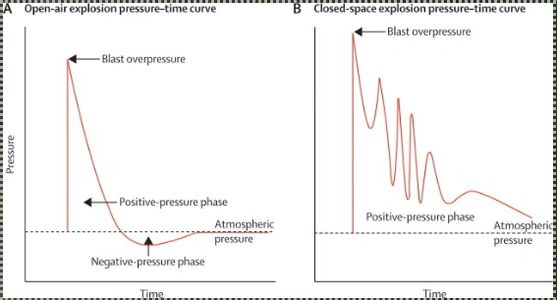

Blast overpressure (BOP)—also referred to as blast overpressure exposure or high-energy impulse noise—is the rapid increase in ambient pressure generated by an explosive detonation, weapons firing, or other high-energy events that produce a shock wave exceeding normal atmospheric pressure. This shock wave is characterised by an abrupt positive pressure phase, followed by a negative pressure (rarefaction) phase, both of which contribute to tissue injury depending on magnitude, duration, and proximity to the source¹,².

Historically, blast injury was understood to predominantly affect air-filled (hollow) organs, including the lungs, auditory system, and gastrointestinal tract. While these organs remain highly vulnerable, contemporary research demonstrates that blast overpressure also exerts significant effects on the central nervous system, even in the absence of overt head impact or structural injury³–⁵. Proposed mechanisms of blast-related brain injury include direct transmission of pressure waves through cranial structures, vascular surge and blood–brain barrier disruption, neuroinflammatory cascades, and axonal and microvascular injury, collectively contributing to blast-induced neurotrauma (BINT)³,⁶.

Importantly, repeated or low-level blast exposures—common in military training and weapons systems operation—have been associated with subclinical but biologically meaningful brain changes, which may not be detected using conventional imaging or neurocognitive testing⁴,⁶.

Overpressure in Enclosed Spaces

The biological effects of blast overpressure are amplified in enclosed or semi-enclosed environments, such as vehicles, buildings, bunkers, or urban settings. In these contexts, blast waves undergo reflection, superposition, and reverberation, leading to higher peak pressures and prolonged exposure durations compared with open-field detonations⁷,⁸. Although structural deformation and energy absorption may partially dissipate blast energy, confinement typically results in greater cumulative pressure loading on exposed individuals.

Theoretical estimation of peak overpressure in enclosed spaces has historically used simplified scaling relationships, such as Weibull-type approximations, which relate overpressure to explosive mass and enclosure volume:

Δp∝(mV)0.72Δp∝(Vm)0.72

where:

- m represents the net explosive mass (adjusted for explosive equivalence), and

- V represents the effective volume of the enclosed space⁹.

While such models are useful for engineering and hazard estimation, they do not fully capture the complex biological effects of blast exposure, particularly on the brain. As a result, modern military and biomedical research increasingly emphasises biological response markers, computational fluid–structure interaction modelling, and objective molecular indicators to better characterise blast exposure and injury risk³,⁶,¹⁰.

The visible and invisible impacts of blast.

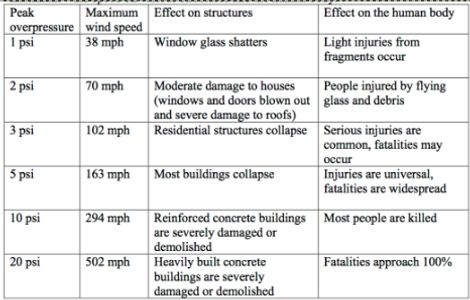

The above table, based on Department of Defense (DoD) data from Glasstone and Dolan (1977)2. and Sartori (1983)3., summarizes the effects of increasing blast pressure on various structures and the human body. This data originates from weapons tests and blast studies to assess the effect of blast overpressure on structures and people.4.

The above graphs show the variation in pressure 'intensity' in an open air explosion as opposed to a closed-space. In short the open air rise quickly to peak and dissipates relatively quickly. The closed-space also rises quickly but the intensity is prolonged even causing 'rebound' type secondary impacts due to reflection, etc.

Data from the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) indicate that explosive mechanisms—including improvised explosive devices (IEDs), mortars, artillery, grenades, and landmines—accounted for more than half of all combat-related injuries sustained by U.S. service members during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan¹¹. Since approximately 2006, blast exposure has remained the leading mechanism of injury among U.S. and allied military forces operating in combat environments¹¹,¹².

Blast-induced traumatic brain injury (TBI) is clinically heterogeneous and may manifest as cognitive impairment, behavioural dysregulation, emotional disturbance, and sensory dysfunction, even in the absence of overt head impact or abnormalities on conventional imaging¹³. These injuries are frequently complicated by comorbid psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which further obscure diagnosis and confound clinical management¹⁴.

At present, assessment of blast-related TBI relies primarily on clinical evaluation, neurocognitive testing, and advanced neuroimaging, all of which have limitations in sensitivity—particularly for mild, repetitive, or sub-concussive injury¹³,¹⁵. In parallel, the U.S. Department of Defense has trialled wearable blast and body-mounted sensor technologies to estimate overpressure exposure during training and combat. While these systems provide useful contextual information, they currently generate semi-quantitative exposure metrics and do not directly measure biological injury or reliably predict clinical outcomes¹⁶.

To address this gap, research groups—including GLIA Diagnostics—are advancing specific and sensitive biomarker-based platforms designed to provide objective, biologically grounded insight into brain injury. In particular, circulating microRNA (miRNA) biomarkers have demonstrated promise in reflecting cellular stress, neuroinflammatory, and neurovascular responses associated with blast exposure and TBI¹⁷,¹⁸. Such approaches aim to support earlier injury detection, improved triage, and more informed clinical decision-making, helping to reduce the long-term consequences of undiagnosed or inadequately managed brain injury.

In parallel, ongoing defence and academic collaborations are exploring the integration of sensor-derived exposure data with biomarker assays, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of injury burden. This combined strategy seeks to deliver actionable, near–real-time insights for clinicians and commanders in both battlefield and acute medical settings, supporting improved immediate care, safer return-to-duty decisions, and enhanced long-term recovery for affected service members¹⁶–¹⁸.

References

- Mayorga MA. The pathology of primary blast overpressure injury. Toxicology. 1997;121(1):17–28.

- DePalma RG, Burris DG, Champion HR, Hodgson MJ. Blast injuries. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(13):1335–1342.

- Cernak I, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Traumatic brain injury: an overview of pathobiology with emphasis on military populations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(2):255–266.

- Mac Donald CL, Johnson AM, Nelson EC, et al. Repetitive blast exposure induces chronic neuroinflammation and white matter changes. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(7):600–609.

- Elder GA, Stone JR, Ahlers ST. Effects of low-level blast exposure on the nervous system. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(17):1529–1549.

- Wolf SJ, Bebarta VS, Bonnett CJ, Pons PT, Cantrill SV. Blast injuries. Lancet. 2009;374(9687):405–415.

- Courtney A, Courtney M. Links between traumatic brain injury and ballistic pressure waves originating in the thorax and extremities. Brain Inj. 2007;21(7):657–662.

- Needham CE, Ritzel DV, Rule GT, Wiri S, Young L. Blast testing issues and TBI: experimental models that lead to wrong conclusions. Front Neurol. 2015;6:72.

- Hopkinson B. A method of determining the pressure-time history in explosive waves. Philos Trans R Soc Lond A. 1914;213:437–456.

- Koliatsos VE, Cernak I, Xu L, et al. A mouse model of blast injury to brain: initial pathological, neuropathological, and behavioral characterization. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70(5):399–416.

- Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. DoD Worldwide Numbers for Traumatic Brain Injury. Silver Spring (MD): DVBIC; 2024.

- Belmont PJ Jr, Schoenfeld AJ, Goodman G. Epidemiology of combat wounds in Iraq and Afghanistan: orthopaedic burden of disease. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2010;19(1):2–7.

- Cernak I, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Traumatic brain injury: an overview of pathobiology with emphasis on military populations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(2):255–266.

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13–22.

- Iverson GL, Gardner AJ, McCrory P, et al. A critical review of concussion assessment tools in military settings. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(8):439–446.

- Rafaels KA, Bass CR, Panzer MB, et al. Brain injury risk from primary blast exposure. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(4):895–901.

- Di Pietro V, Porto E, Ragusa M, et al. MicroRNAs as novel biomarkers for traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(18):1–14.

- Atif H, Hicks SD. A review of microRNA biomarkers in traumatic brain injury. J Exp Neurosci. 2019;13:1–12.