Throughout history, the psychological consequences of combat have been recognised under different names. During the American Civil War, the condition was referred to as “soldier’s heart”; in World War I, it became known as “shell shock”; and during World War II, it was described as “battle fatigue” or “combat fatigue”. Today, these syndromes are collectively recognised as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

PTSD is characterised by a constellation of psychological and physiological symptoms, including intrusive recollections of traumatic events, nightmares, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle responses, emotional dysregulation, and heightened anxiety. While acute stress reactions may be expected following traumatic exposure, the persistence of these symptoms for weeks to months reflects the development of a pathological stress response requiring clinical attention¹.

Although the formal diagnostic term PTSD was only introduced in the late 20th century, the condition itself has been documented for centuries. Its modern conceptualisation emerged during World War I, when large numbers of soldiers exposed to prolonged artillery bombardment and trench warfare returned with profound psychological impairment. At the time, symptoms were attributed to physical concussive forces from exploding shells, leading to the term “shell shock.”Early descriptions emphasised confusion, disorientation, tremor, and emotional collapse². However, similar symptoms were soon observed in soldiers who had not been exposed to blast, challenging purely mechanical explanations.

This misunderstanding contributed to the erroneous belief that affected soldiers were exhibiting moral weakness or cowardice. Treatment approaches were minimal and punitive by modern standards, often consisting of short periods of rest followed by pressure to return to combat. Although historical records suggest that approximately 60–70% of affected soldiers returned to duty, many did so with persistent psychological injury, laying the foundation for the contemporary understanding of PTSD as a chronic and disabling condition rather than a transient failure of resilience²,³.

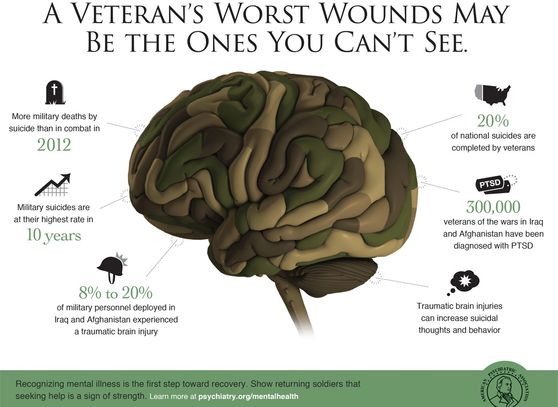

TThe conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan were associated with a substantial increase in the number of veterans experiencing traumatic brain injury (TBI), driven largely by blast exposure. Data from the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) indicate that approximately 20–23% of combat casualtiesfrom these conflicts involved some form of brain injury⁴. In addition, studies of blast-related trauma show that 60–80% of service members sustaining other blast injuries also experience a concurrent TBI, underscoring the frequent co-occurrence of brain injury in modern combat environments⁵.

The vast majority of deployment-related TBIs are classified as mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). DVBIC surveillance data indicate that more than 80–90% of all TBIs diagnosed in U.S. service members are mild, reflecting both the prevalence of blast exposure and the difficulty of detecting subtle neurological injury in operational settings⁴,⁶.

The burden of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among veterans varies by service era. Among veterans of Operations Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Enduring Freedom (OEF), approximately 11–20% experience PTSD in a given year, while an estimated 12% of Gulf War (Desert Storm) veterans are affected annually³,⁷. Importantly, TBI and PTSD frequently co-occur. Among OEF/OIF veterans presenting with PTSD, approximately one-third have a history of mild TBI, and nearly half have sustained multiple or more severe concussive injuries, highlighting the complex interaction between psychological trauma and brain injury⁸.

Blast-related mTBI appears to differ from civilian concussion, producing distinct symptom profiles and recovery trajectories. Veterans commonly report persistent post-concussive symptoms lasting 18–24 months or longer, substantially exceeding typical recovery timelines observed in civilian populations⁵,⁸.

The economic and social consequences are considerable. RAND analyses estimate that among the approximately 1.6 million U.S. service members deployed since 2001, the combined costs of PTSD and major depression alone range from USD $4.0–6.2 billion within two years post-deployment, driven by healthcare utilisation, disability compensation, and lost productivity⁹. TBI adds significantly to this burden, particularly when injuries are repetitive or inadequately identified early⁴,⁶.

The consequences extend beyond morbidity to mortality risk. In Australia, while suicide rates among serving and reserve defence personnel are lower than those of the general population, ex-serving personnel—both men and women—exhibit higher suicide rates than their civilian counterparts¹⁰. Between 2001 and 2017, 419 suicides were recorded among serving, reserve, and ex-serving Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel who had served since 2001¹¹, underscoring the long-term mental health impact of service-related injury and trauma.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of traumatic brain injury (TBI), associated post-concussive symptoms, and common comorbidities such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) presents significant clinical challenges. At present, no available screening instrument can reliably establish a definitive diagnosis of TBI, and the clinical gold standard remains a comprehensive assessment conducted by an experienced clinician, often requiring longitudinal follow-up. Existing screening tools used across military, veteran, and civilian healthcare settings are intended to identify individuals who may require further evaluation, rather than to confirm injury or define biological status. This persistent diagnostic uncertainty—particularly in mild, repetitive, or blast-related injury—highlights the need for objective molecular measures, such as circulating microRNA (miRNA) biomarkers, which have demonstrated potential to reflect underlying neurobiological injury and stress responses associated with both TBI and PTSD, and to complement clinical assessment with biologically grounded insight¹²–¹⁵.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington (DC): APA; 2013.

- Jones E, Wessely S. Shell shock to PTSD: Military psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War. Hove (UK): Psychology Press; 2005.

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13–22.

- Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. DoD Worldwide Numbers for Traumatic Brain Injury. Silver Spring (MD): DVBIC; 2024.

- Mac Donald CL, Johnson AM, Nelson EC, et al. Blast-related traumatic brain injury in military populations. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(7):600–609.

- Helmick K, Schwab K, Barker F, et al. Traumatic brain injury in the U.S. military: epidemiology and outcomes. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30(1):1–8.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD – How Common Is PTSD in Veterans?Washington (DC): VA; 2023.

- Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Cox AL, Engel CC, Castro CA. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(5):453–463.

- Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, editors. Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation; 2008.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Suicide and self-harm in the Australian Defence Force. Canberra: AIHW; 2020.

- Department of Veterans’ Affairs (Australia). National Veteran Suicide Prevention Strategy—Supporting Data. Canberra: DVA; 2021.

- Di Pietro V, Porto E, Ragusa M, et al. MicroRNAs as novel biomarkers for traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018;35(18):1–14.

- Atif H, Hicks SD. A review of microRNA biomarkers in traumatic brain injury. J Exp Neurosci. 2019;13:1–12.

- Balakathiresan NS, Chandran R, Bhomia M, et al. Serum and amygdala microRNA signatures of posttraumatic stress disorder in a mouse model. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84667.

- Wingo AP, Almli LM, Stevens JS, et al. DICER1 and microRNA regulation in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(6):592–602.